While we are in the closing days of the annual (war on) Christmas season, I wanted to address a meme that floats around yearly. It showed up in my Facebook feed a bunch of times and is a meme spread by FAUX news for the last few weeks.

This clever sounding sound-bite makes a clear point: Christmas is the only holiday we are allowed to care about. Not Hanukkah, not Kwanza, not the solstice, definitely not the new year, nor the oxford comma. I expect some people promoting this meme are generally well-meaning and not the douches they seem to be. So with some limited holiday spirit in mind, I want to take a minute to let you know what 'It's not happy holidays, it's Merry Christmas!' means and doesn't mean to me.

What it means: It means you fail to recognize your Christian privilege. You assume that since Jesus is important to you, he should be important to them too. You assume that since in your tradition you choose to have the winter solstice represent the birth of Jesus that everyone else should too. No matter what someone else's religious, non-religious, cultural, tribal, or other background is, they must enjoy this time of year as you deem fit.

What it doesn't mean: It doesn't mean that you are expressing goodwill or joy or happiness or any other positive feeling to others (Christian or otherwise). You are making a political statement. Your 'Merry Christmas' is not actually a message of hope that I am merry on the 25th of December. It's a demand that I prostrate myself to your overbearing and extremely limited interpretation of Christianity.

What it means: It means that the first amendment means little to you except a protection of your religious beliefs. When states make laws demanding that stores are closed on Christmas (interfering with the free market), it has to be (and has been) justified from a secular standpoint. Of course everyone knows these kind of laws are only established to benefit Christianity, the justification promoted uses a reach around approach to avoid this obvious position.

What it doesn't mean: It doesn't mean that all people in this country are equal under the law. Or maybe I should say that all people are equal under the law, but some animals are more equal than others (thank you public education).

What it means: It means that when a stranger tells me Merry Christmas, I now have to wonder if they actually are expressing well-wishes and happiness or being douchebags like the people who post pictures like the above on Facebook. For that, I want to wish you a:

(I wasn't going to write this post, but then I came across the Grumpy Cat picture, which made me laugh so hard, my 11 year old wanted to know what was so funny. After that I had to write this post. So thanks and Happy Holidays to all the Grumpy Cats in the world (and a Merry Christmas to everyone).)

- Home

- Angry by Choice

- Catalogue of Organisms

- Chinleana

- Doc Madhattan

- Games with Words

- Genomics, Medicine, and Pseudoscience

- History of Geology

- Moss Plants and More

- Pleiotropy

- Plektix

- RRResearch

- Skeptic Wonder

- The Culture of Chemistry

- The Curious Wavefunction

- The Phytophactor

- The View from a Microbiologist

- Variety of Life

Field of Science

-

-

Earth Day: Pogo and our responsibility2 months ago in Doc Madhattan

-

What I Read 20243 months ago in Angry by Choice

-

I've moved to Substack. Come join me there.4 months ago in Genomics, Medicine, and Pseudoscience

-

-

The Site is Dead, Long Live the Site2 years ago in Catalogue of Organisms

-

The Site is Dead, Long Live the Site2 years ago in Variety of Life

-

-

-

-

Histological Evidence of Trauma in Dicynodont Tusks6 years ago in Chinleana

-

Posted: July 21, 2018 at 03:03PM6 years ago in Field Notes

-

Why doesn't all the GTA get taken up?7 years ago in RRResearch

-

-

Harnessing innate immunity to cure HIV8 years ago in Rule of 6ix

-

-

-

-

-

-

post doc job opportunity on ribosome biochemistry!10 years ago in Protein Evolution and Other Musings

-

Blogging Microbes- Communicating Microbiology to Netizens10 years ago in Memoirs of a Defective Brain

-

Re-Blog: June Was 6th Warmest Globally10 years ago in The View from a Microbiologist

-

-

-

The Lure of the Obscure? Guest Post by Frank Stahl13 years ago in Sex, Genes & Evolution

-

-

Lab Rat Moving House13 years ago in Life of a Lab Rat

-

Goodbye FoS, thanks for all the laughs13 years ago in Disease Prone

-

-

Slideshow of NASA's Stardust-NExT Mission Comet Tempel 1 Flyby14 years ago in The Large Picture Blog

-

in The Biology Files

Discussions on the interface between Science and Society, Politics, Religion, Life, and whatever else I decide to write about.

My Favorite Time of the Year

|

| From here |

FYI: The assignment is to write an essay of 1000 - 1500 words for a lay audience of science enthusiasts that incorporates at least primary research papers on a eukaryotic microbe. (Microbe being defined in the course as an organism that exists primarily as a single celled organism, thus excluding microscopic multicellular animals.) Students were allowed to write in any voice and use any style of writing.

If you read through an essay, please leave a comment for the student.

Once unto the breach, dear friends

A short time ago, as I headed to teach one of my classes, I saw an older white guy writing a chalk advertisement on the pavement in front of the student union. The advertised talk seemed to be a presentation or discussion of the problems with evolutionary theory. Since I did not have my son that evening, I decided to attend.

This was not a talk, presentation, or discussion of the problems with evolutionary theory. No, this was nothing more than a collection of well-disputed creationist talking points hiding under the auspices of an honest scholarly seminar.

I learned several things because of my attendance, none of which the presenters wanted me to learn I expect.

1. The Importance of Authority

|

| I mean 'Really!?!?' |

The argument from authority came up throughout the talks. Initially it was in the form of the speakers credentials. I do not have a problem with this in principle, it is important to know why we should be listening to these people. However, when you overinflate someone's credentials to make them seem to be experts, problems ensue. One of the speakers studied evolutionary biology...during their fisheries and wildlife training! You know because nothing says evolutionary biologist like a fish and wildlife degree. We were also told that both presenters taught at colleges and universities, although we were not told which ones and in what capacity. Based on the constant lies and half-truths stated during the presentations, I expect that these talks at my university will constitute 'teaching at my university' in the future.

The argument from authority continued throughout the talks in the form of slides containing nothing but a quote from some person. Almost always these quotations came from creationists. Using quotes can be a powerful form of argument, if it is backed up with some substance. Using the quote 'To be or not to be' as a preface to address teenage angst and suicide prevention can be powerful approach. Using the quote 'To be or not to be' as evidence that teenagers contemplate suicide as demonstrated by Ophelia drowning herself, is not a powerful argument and contains an obvious WTF*. This is the approach the presenters took. "Creationists have a problem with evolutionary theory, so here are quotes by other people (almost all of which were not biologically trained) that agree with us." This is akin to me using the picture below on the left and stating that the presenters are lying assholes with absolutely no shame, no soul, and no business setting foot on a college campus. Then advancing to the slide on the right and noting that Mr. Stratten supports my position and thinks I may be wasting my time.

|

| Quote Support |

|

| Average donkey |

The final argument from authority comes from the reference to the bible. By and large, the presenters tried to bring up neither god nor the bible, but they had to early on to establish their position. Without the crutch of god and the bible, their points would have been obviously ridiculous. However, once god and the bible are established as the counter-argument, this ridiculousness is given a free pass. The debate then becomes the bible/god vs evolution comparison. Since all the bible/god position has for evidence is the bible (thus an absolute argument from authority position), the evolution position has to be cast in the same light, it's all argument from authority. We can ignore the evidence and just focus on who said what, never mind why they said it.

2. The Gish Gallop

You may have heard of the dreaded 'Gish Gallop.' If not let me introduce it to you. The Gish Gallop is a debating technique perfected by Duane Gish, who, not surprisingly, is a creationist. Basically you take a complex issue and move from topic to topic using lies, out of context data, lies, half-truths, strawmen, lies, misconceptions, lies, etc. during a debate. Your opponent does not have sufficient time to rebut all of these lies and ends up discrediting one or two at most during their time. This leaves the audience thinking that the other 15 talking points were valid (or at least not discredited). The talk I attended was nothing more than an extended, 90 fucking minute, Gish Gallop. This is a primary reason why scientists should not debate creationists. (Remember we were told not to look anything up, which prevents a suspecting mind from realizing the presenters were full of shit in real time.)

Topics covered, using frequent lies, out of context data, half-truths, full lies, strawmen, lies, misconceptions, and lies, included but were not limited to the following:

- Racism is a direct outcome of evolutionary theory, yet Genesis shows that we are all equal. So no racism in the bible or before 1859.

- Cells are literal factories. There is no metaphor to see here, move along

- Haeckel's embryos and peppermoths FTW!

- There is no such thing as junk DNA.

- The Cambrian explosion occurred in a short time frame, because you know the word explosion.

- Darwin was concerned about the dearth of fossils (true, be we found a couple more since 1859 /snark).

- Pictures of ancient organisms often colorized, but we do not actually know what color they were. Therefore evolution not correct. Q.E.D

- Piltdown man was a hoax (no mention of the fact it was exposed by scientists).

- and as if the arguments could not get any worse: the presenters stated that Lucy is likely male1, yet has a female-associated name. The obvious conclusion from this is that evolutionary theory is wrong.

- Plus there was a slide with this on it2

|

| Damn you New Scientist |

3. Data vs. interpretation

I will give the presenters credit in that they had a thesis for their talk. At least they had a point that they came back to with some regularity. I also think this is an important point and from that standpoint I agree with the presenters. Of course this is like saying the presenters and I both agree that knives are sharp, but the presenters think the best way to show this is to replace the balls in a ball pit with machetes and sharing said pit with a sugar-hopped up toddler birthday party.

A recurring theme was that they had no problems with the data (not true of course), but simply with the interpretation of the data. One of the classes I teach is an advanced microbiology course (in fact this is the course I was heading towards when I saw the old white chalk-writing guy). We spend a great deal of time learning how to evaluate data and critique interpretations of data. This is not easy stuff, in fact I will go so far as to say it is kind of fucking hard!

Regardless, the argument between evolution and the bible was cast as simply one of interpretation.

If we look at the molecular evidence we see protein sequences are more similar in related organisms. The same is true if we look at DNA sequences. Evolutionary biologists conclude this supports common decent, creationists conclude this supports common design. It's simply an issue of interpretation and there is no way to resolve these different interpretations. Therefore both are equally valid! Except not really, because all the data is bad.They argue that all the data is bad later on and fail to address the fact that they directly contradict themselves. As they lay it out, maybe a case could be made. But their case is incomplete. First, many amino acids that make up a protein sequence behave similarly. Thus, the fact that more closely related organisms have identical sequences whereas more distantly related organisms have slightly different sequences supports common decent not common design, unless we want to argue that the designer is lazy. Second, the DNA encoding a protein sequence is redundant. In other words different DNA sequences give rise to the exact same amino acid. The fact that more closely related organisms have identical DNA sequences whereas more distantly related organisms have slightly different sequences, yet make the exact same protein supports common decent not common design, unless we want to argue that the designer is infinitely lazy. Third, within the mammalian genome reside the carcasses of dead retroviruses. What is surprising is that these carcasses are positioned in the exact same place in related organisms and then absent in more distantly related organisms. Like the dead on election day, the don't do anything. They are just there. More molecular evidence that supports common decent, not common design, unless we want to argue that the designer is eternally drunk on top of being infinitely lazy.

This type of argument occurred several times during the talk. The data is fine, it's simply interpretation. What irks me most, at least at the time I am writing this, is that when I write papers, give presentations, etc. I try to undermine my own ideas. I raise any conflicting data or alternative ideas. I, and most other scientists, do this because we want to get at the truth. At the very least, we do not want to make fools of ourselves. These kind of one-sided presentations go against all of my training. It disgusts me in a political discussion (most choices are difficult and have pros and cons, a healthy discussion of both is warranted yet rarely occurs). But it cuts deep to my core when this one-sided approach is given under the guise of being an evidence based talk.

Question Time

And now it was (FINALLY) time for questions. Albeit questions with some rules. (Remember this is the 'don't look things up' talk, so rules regarding questions should be expected.) We were told one question per participant, which makes sense. We were told that we could ask additional questions if there were no first time questioners. We were also instructed not to rebut the answers given. This makes sense at face value, as you don't want to have simple argument, but is also a cop-out allowing the presenters to

I tried to ask a bigger picture question rather than one that simply disputes one of the hundred or so misconceptions, lies, or fallacies the presenters made. I decided on two, but only asked one. (Dealing with fucktards is important to me, making sure I get to call my son and say 'Goodnight' and 'I love you' is more important. I had to leave during questions to make sure the latter happened.) The question I did not ask was:

Do you think that the tens of thousands of biologists in the world teaching evolutionary principles are stupid, evil, or a combination of the two? Because if the points you have made were actually true, it seems like the conclusion has to be something along these lines. I ask, because essentially all evidence gained in support of evolutionary theory was obtained by god-fearing individual scientists. Indeed all the interpretations that have led to the modern theory of evolution was developed primarily by Christians. Hell, even the director of the National Institutes of Health, Francis Collins, is an evangelical Christian who has written a couple of books about God and biology.I like this question because for 90 minutes the presenters had presented a completely one-sided

However, I asked a different question. Remember one of the points they came back to several times was the issue of data versus interpretation. This is an important point in science, which I stress in the courses I teach. There are questions regarding data, how it was obtained, what was observed , etc. However, these are different from the questions regarding interpretation. With interpretation, the authors (generally speaking) put their data in context with the broader body of knowledge. They go beyond telling you what the data is, and tell you what the data means. This is what the presenters did frequently throughout the talk. They took 'data' (I purposely use quotes.) and interpreted for the audience. The problem is that the presenters never put the data in context of our understanding of the universe. Regardless, one of their major theses was that the difference between creationists like them and biologists was simply one of interpretation. The presenters had no problem with the data (except for when they did i.e. fossils, dating, etc.), only with interpretation of the data. This is the background from which where my question originated.

At the beginning of your presentations you noted that observation and experimentation were tenets of the sciences (I know, I know). However, you failed to mention that the power of science comes from its ability to make predictions about the future that are accurate. Without this aspect of science, science is no more useful than religion or astrology (Yes, I know, but realize I had been sitting through an hour and a half of this shit, I earned this!). You noted that you believe much of the issue is due to differences in interpretation, but not the data. However, numerous cases you used throughout your talk are not differences in interpretation. For example, you argued that DNA and protein similarity can be interpreted from an evolutionary viewpoint, but also from a creationist viewpoint, because an intelligent designer (God of the bible) would use similar parts. However, this is an example of Monday morning quarterbacking, because the similarity of DNA and protein was a prediction of evolutionary theory. Before we had the methods to analyze these molecules, we predicted related organisms would have related DNA and protein. You also brought up the fossil Tiktaalik (and I thank the presenters for helping me get the pronounciation correct). This fossil was unknown, but based on evolutionary theory, Neil Shubin predicted when this fossil should occur in the record, went to rocks of this age, and was fortunate enough to find it. This was a prediction of evolutionary theory. Clearly evolutionary theory passes this aspect of science, making accurate predictions. My question to you is what predictions have creationism made that have subsequently been found to be true?The sad part is they gave me answer. Want to know what it was? Junk DNA2. Fucking junk DNA. Now we were directed to not get into a back-and-forth with the presenters, and I understand why that was requested,

The presenters asked me why I said that. I restated that junk DNA is not a tenet of evolutionary theory, it is neither required nor omitted. In fact, we have long known that bacteria essentially lack junk DNA. (This is not a secret, so it makes me wonder why they think junk DNA is a tenet of evolutionary biology.) Regardless, it is not up to me to explain it because it was their thesis that junk DNA was a tenet of evolutionary theory, so it was up to them to demonstrate this was the case.

At this point the moderator intervened and said 'Well stasis' (the fact the some fossils look just like modern animals). This was one of the 100 or so Gish gallop points, but as far as I'm concerned is basically a 'why are there still monkeys?' argument. Sharks have not changed much, but many descendants of ancient sharks have changed. Many microbes are round and have been for ~4 billion years, that's the ultimate stasis! Yet look at how things have changed in many of their descendants! Anyway at this point, I simply noted that stasis is not a good rebuttal, but that they did not want the meeting to turn into a debate. (Rightly so, remember in a he-said, she-said debate, truth loses.) Plus, I much preferred to wish my son good night and tell him I love him.

1 This argument seems to come from a historian of science, not a paleontologist nor otherwise trained biologist. The idea that Lucy is male is not accepted in the field.

2Fuck you very much New scientist/ENCODE.

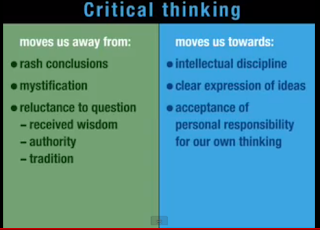

Teaching Critical Thinking

One question I grapple with is 'how do we get students to ask questions about, or rather to question, peer reviewed research papers?' This is based on my experience that undergraduate students and even many introductory graduate students have difficulty grasping the concept that there may be issues or even important problems with peer reviewed research. Part of this is based on an inherent appeal to authority/self confidence issue, how could a lowly undergraduate find something problematic with a paper written by Ph.D., or equivalently trained, scientists.

However, the question I am grappling with is just a subset of the more important issue, how do we teach students how to ask the 'right' questions. The key here being 'right.' This is a fundamental aspect of critical thinking. Being able to identify the assumptions, biases, controls needed, discrepancies, etc. in an argument, and a peer reviewed research paper is nothing if not an argument. I find the most successful approach is to identify these, and other, points by asking questions. Again these question have to be the 'right' questions.

In my advanced undergraduate class, I can usually classify my students into 3 categories: the non-questioners, the trivial questioners, and the rare critical thinking questioner. By the end of my course, I want my students to find themselves generally in this latter category.

In the first category, the non-questioner, we find the shy students who are uncomfortable speaking up. This silence could be the result of inherent shyness, poor classroom experiences, or even cultural issues. In fact, this point of 'cultural issues' reminds me that it is important for me to remember that women and minorities are frequently ignored or blatantly omitted from discussions. In my experience, there are as many if not more women promoting the discussions in my course as men. Regardless, I try to address the issue of cultural differences early by calling on women and minorities during our

discussion sessions. Included in this category of students are those who are not confident with the material and thus do not want to speak up for fear of saying something stupid. I provide many resources and tools to help bring students up to speed if they are missing some background, so I tend to be less sympathetic with these students because they, by definition, must be aware of their deficiencies and choose not to address them. Of course, it takes awhile to separate these students from those who are shy, but it is disheartening to identify a student as being intellectually lazy, lazy in general, or indifferent. To be clear, I have had students that lack some of the foundational material needed for my course that have worked hard to address these issues, and I help them as much as possible, having one on one meetings as much as they need to go over concepts, specific papers, etc. I love these students, because they have a drive that is infectious. Getting back to the shy students, how can I help get them engage in the course, such that they can move to category 3 and without having to change their personalities? For these students, all students actually, I have online components to the course. In addition to in class discussions, I have an online forum to initiate new discussions or continue discussions started in the classroom. This provides a place for those students who are inherently shy and students who are not comfortable thinking on their feet, which is what the classroom discussions entail. Students can use these forums to ask broad questions, initiating discussions beyond the minutiae of the papers they read. Students can also ask for help if there is something in the papers, a method, conclusion, etc. they do not understand, and students can help their colleagues by answering those requests for help. While I monitor the discussion boards, I refrain from commenting as much as possible, such that it quickly becomes a student-driven environment. While not perfect, there are mechanisms to promote moving students from category 1 to category 3.

The second category: the trivial questioner, is the place I work the most. Not that a specific student is a constant trivial questioner, but rather it is a constant place we come back to in class. This is not a problem because it does serve as a constant 'teachable moment.' The trivial questioner falls into the meme that there are no stupid questions. Of course there are stupid questions! In fact, the 'there are no stupid questions' comment is itself a stupid comment. I understand the 'there are no stupid questions' concept, but it is used with the tacit understanding that everyone is acting in good faith. This is seldom the case. For example we have Ken Hamm's 'Were you there?' question. This question is bullshit and not acting in good faith. The fact he encourages ten year olds to ask this question just serves to exemplify the moral vacuum in which Hamm resides. Hamm knows this question is a bullshit question, but it is a nice soundbite gotcha-sounding question to the masses. However, the ten year olds Hamm sends out to 'ask' questions do not know why this is bullshit, and that is his goal. However, we can use it as a teachable moment. The problem, in my opinion, is that Hamm knows many children would never ask the question, but will think the question and then answer it for themselves. In my course, there are many 'were you there?' type questions. Not necessarily from the Hamm perspective, but from the 10 year old perspective of 'this sounds good, I'll go with it' perspective.' These kind of questions are particularly present at the beginning of the course and I like to think I help move the students into the 3rd category. It's possible that I push these students into the 1st category, but I doubt that based on the quality of the discussions as the semester progresses. By way of example, every year when discussing a paper using a mouse model, the question will arise 'well I am concerned that the study only used female mice and I wonder what the data would be if male mice were used?' This kind of question is relatively easy to come up with because we teach students 'black and white' thinking, everything is a binary decision. So when the student reads the methods and materials and sees '20 female C57/B6 mice were....' the student immediately thinks 'male' or vice versa in a 'tell me the word that pop into your head when I say...' kind of way.

So how do I encourage questions/comments of these 2nd category students without pushing them into the 1st category? What I have found works is to mimic Socrates, I ask questions. For example...

Finally, we come to the third category: the critical thinker questioners. For these students, I can only refine their skills, improve their writing, and expose them to new and interesting areas. Almost uniformly, these students have research experience and likely significant experience. However, these students almost certainly have holes based on the areas they have been exposed to. These students know the potential issues in the area they are familiar with, but lack the similar approach/mindset in the areas they are not familiar with. This is one of the reasons it is essential for scientists to read well outside their fields. Breadth of knowledge promotes a better assessment for how your studies fit into the broader world of science. This increases the impact of your research not only from the study in question, but also in the questions you ask in the first place.

FYI. While I have categorized student comments/questions into 3 groups, no one student (nor the instructor) fits into a given group. Furthermore, I love my course because I learn so much from the students, even those that tend to cluster in a specific category. The lessons I learn may vary, but I learn important concepts, holes, insights from all three groups. I thank the students from previous years for helping me develop these insights and to improve my courses.

|

| Why We Care About Critical Thinking |

In my advanced undergraduate class, I can usually classify my students into 3 categories: the non-questioners, the trivial questioners, and the rare critical thinking questioner. By the end of my course, I want my students to find themselves generally in this latter category.

In the first category, the non-questioner, we find the shy students who are uncomfortable speaking up. This silence could be the result of inherent shyness, poor classroom experiences, or even cultural issues. In fact, this point of 'cultural issues' reminds me that it is important for me to remember that women and minorities are frequently ignored or blatantly omitted from discussions. In my experience, there are as many if not more women promoting the discussions in my course as men. Regardless, I try to address the issue of cultural differences early by calling on women and minorities during our

|

| The Shy Student |

|

| Were you there? Only applies to science not the New Testament. |

So how do I encourage questions/comments of these 2nd category students without pushing them into the 1st category? What I have found works is to mimic Socrates, I ask questions. For example...

I am concerned that the study only used female mice and I wonder what the data would be if male mice were used?

Why do you think this might make a difference? I agree that there are important differences between females and males, I'm wondering how you think these differences apply to this study?

Well there could be differences due to hormones or something...

That's a great point, because that is clearly the case in certain instances like Paracoccidiodes infections. Is there anything in this system that makes you think there is would be a sex-based difference?

.....

Ok that's a good point at face value, but maybe needs further consideration, did anyone have additional issues with this study?The point is to encourage/require the students to have a scientific justification for their concerns, questions, critiques. This, in my opinion, is the most difficult thing the students can learn and that I can teach. The point is that I need to teach the students how to question the studies, but also to question their own questions/concerns. But, I want to emphasize that it is ok to be wrong! We talk about well conducted studies that have generally solid conclusions and identify potential concerns. These concerns may not change the overall conclusions, but do raise concerns with sub-conclusions that may not be valid. In fact, the introductory paper we are discussing is the one I railed on previously. We will also be considering the press release. This is a change from the last couple of years when we discussed a well written, described, and assessed paper. I'm interested in how this approach works.

|

| Own this book!!! |

Finally, we come to the third category: the critical thinker questioners. For these students, I can only refine their skills, improve their writing, and expose them to new and interesting areas. Almost uniformly, these students have research experience and likely significant experience. However, these students almost certainly have holes based on the areas they have been exposed to. These students know the potential issues in the area they are familiar with, but lack the similar approach/mindset in the areas they are not familiar with. This is one of the reasons it is essential for scientists to read well outside their fields. Breadth of knowledge promotes a better assessment for how your studies fit into the broader world of science. This increases the impact of your research not only from the study in question, but also in the questions you ask in the first place.

FYI. While I have categorized student comments/questions into 3 groups, no one student (nor the instructor) fits into a given group. Furthermore, I love my course because I learn so much from the students, even those that tend to cluster in a specific category. The lessons I learn may vary, but I learn important concepts, holes, insights from all three groups. I thank the students from previous years for helping me develop these insights and to improve my courses.

How to study: a re-repost

This seems timely to repost.

Since a new semester is about to begin I think a post on how to study would be apropos. So here is an advice column for students looking for some techniques to improve their study habits. I am not an expert in learning, but I am an expert in being a college student with no fucking idea how to study and had to figure it out over the course of a year or two. I was one of those students who didn't have to do much to maintain an A/B average in high school. Although I was exposed to study skills and habits while in high school, none of it stuck because I really didn't need to study to do reasonably well. So here is what I learned that worked for me. If you have your own successful techniques, please feel free to add them in the comments.

Learning is an active process, it requires energy. It may not be as physically taxing as a 45 minute work out, but then again you may not be doing it right. What I discovered is that I learn when I do things, when I engage the material, when I'm an active participant. If it's a couple of days before the big exam and you're wondering to yourself 'What's the best way I can study? I know, I'll take some time to play online and get some tips.' Well, if this is you, you're fucked or at least I don't have anything for you. Come back after your upcoming exam, my advice might help you for the next exam. Right now, you are in cram mode, so you better start cramming and not wasting your time reading blogs. I will admit that cramming works, to a degree. Cramming is a short term solution, getting enough material under you belt to survive or even succeed at the exam. But it's a long-term problem. Are you really in college to survive exams and classes? That was really high school wasn't it? Cramming is problematic because the material is never actually learned, it may come up again on the final, it will likely be important next semester or the semester after that in your more advanced classes. Learning and cramming both take energy, but the former is far less stressful and provides both short-term and long-term gains.

Step 1. Find an environment to study in. Ultimately this became at my desk in the bedroom of my apartment. I also kept my stereo close by set at police notification level. I learned quickly that I could ignore the music, but sounds from the street, from the kitchen/dining/living room area, or from anywhere outside my room were distracting. To this day, when I'm working on grants or papers and do not want to be disturbed, I close my office door and crank up some music. Although I am a chaotic person by nature, my desk was neat and organized. I needed a place to work comfortably and that was it. My textbooks and notebooks were stacked in/on some milk crates I used for shelves. (These of course were the store bought kind of 'milk crates' not the easily available sturdy and inexpensive milk crates available behind 7/11s, like the one across the street of my apartment. Although if they were the illicit version, which they weren't, they would have been returned when I moved to go to graduate school.)

$0.69 for 3 in 1989

|

Step 2. Get a bunch of notebooks. I used spiral bound notebooks available for next to nothing at drug stores. Of course these notebooks will have absurd cover designs or pictures you would never in a million years gravitate towards (see picture of my Molecular Biology notebook). That's not the point. The point is what's inside the notebook, and that will be gold. I mixed up the designs on the notebooks I bought so I could easily identify which one I wanted. The alternative is to be flipping through them wondering if this is the black notebook Im looking for. Get one notebook for every class you take (except maybe for the golf/tennis/etc classes). Any class that has a lecture has its own notebook. No cheating by getting a three-subject notebook. Also, get a couple of additional notebooks.

These things are evidence of evil

|

Since you're at the drug store all ready, get some pens and pencils. I love pens, but despise cheap ass ball point pens. You'll be using these a lot, so get pens/pencils you are comfortable with. Make sure you get a variety of colors. I survived with black, blue, and red, but there is a veritable palate of colored inks now. Get what you love or at least can tolerate. I prefer mechanical pencils, but if you get classic ones, you better kick in for a decent pencil sharpener or two. Also grab some highlighters also in assorted colors.

Step 3. Do the readings strategically. Chapter 3 is covered Wednesday? Read it through by Tuesday night. That isn't very strategic is it? The strategy is to skim read the text. Get a sense of what's in there and what will be the likely topics and points for the upcoming lecture. You don't need to be more than familiar with the material. (In the case of labs, this is not true. You must be intimately aware of the material, because you will be using that information in the lab. Hell, there may even be a quiz on the lab manual!)

Step 4. Go to class. Although you probably couldn't pass a quiz on the readings material, the vocabulary is familiar. Now you already know a bit about the upcoming lecture. Gather up your pens and pencils and one of the extra notebooks. Leave your textbooks at home, along with the highlighters, and other notebooks. You don't need much.

Get to class on time and get a good seat. In large classes, I recommend a seat near to the front and in the middle where the professor can actually see you. Why? Psychology that's why. Take two students doing equally well, one student the professor recognizes, even if there is no name associated with the face, and one student the professor has barely, if ever, seen. If both come to discuss an issue regarding an examination or writing assignment, which one will have at least a sub-conscious advantage?

Open your notebook to page 1 get out a couple of writing implements and get ready. If the professor has handouts or, god forbid, print outs of the slides, then definitely pick them up, but DONT use them during the lecture (with rare exception). Your job is to take a shit ton of notes. Don't worry about neatness and perfection, just get the stuff written down. Write down the points on the slides, the drawings, incorporate what the professor is saying. The very act of writing things down is helping you learn the material! 'But we have the slide print outs, so why write stuff down?' you ask. In my more youthful days I would have responded with 'Because we didn't have the material presented to us, so stop being so fucking needy.' But in my dotage I think an example is better. What is another name for a television? Did 'idiot box' spring to mind? There's a reason for that. Some people watch tons of TV, these are not inherently the most educated people in the world. My mother loved to watch soap operas during the 70s, hours of soap operas. She was not an expert in social interactions because of this nor was she an expert story teller, she just watched a lot of soap operas. This is one of the biggest impediments to learning, fucking handouts. Remember I said learning was an active process. Lectures are not television. You should be doing something not just watching. The problem with handouts is that it facilitates the TV watching mentality. There are reasons to hand out the notes, which is why you are collecting them, but wait until later to use them. For now, take a shit ton of notes. Do not be tempted to put notes in the margin of the print outs, you bought the cheap ass notebook, so use it. (Plus you'll want a pristine copy of those hand outs for later.) So, you were in class sitting in a strategic location, you took a shit ton of notes, now what? Go to your next class and repeat using the same notebook.

Notes on chromosomal

melting temps.

|

Step 5. THE MOST IMPORTANT STEP: The next day. So you went to all your classes, even the ones you think are boring, and you took a bunch of notes, even on things you think you know already. Now what? Hang out with friends, watch TV, play some Xbox, then go to bed and the next day go to all your other classes. At some point on this second day, you need to carve out some studying time. When depends on your schedule. I did this in the mid-late-afternoon, because I was generally done with classes then. Go to your studying environment, get out your notes from yesterday, one of the fresh notebooks that will be specific for a specific class, any handouts, and your textbook. Now you will rewrite your notes in a more organized and legible manner. As you rewrite, you will refer to the text for additional points, and in your class-specific notebook you can either incorporate the textbook material or simple refer to the page numbers/figure numbers. Either redraw or cut out the handout figures you need and add them to your notebook. This could take as long as the original lecture, but probably won't. Regardless, you are now learning some serious material. The act of rewriting helps embed the information into your memory, by organizing the material in a manner that works for you (which is probably like it was presented) you are thinking about the material in total not simply one fact after another. You are also reading the text in a more in depth way, which is easier because you already skimmed it and went to the lecture. Do this for those boring easy classes too. It helps maintain good study habits and instead of simply learning the material, you'll own it. Another benefit is that if you do this, you will know before the next lecture what material you may not understand. This gives you a ton of time to meet with your colleagues, TAs, professor to get things straight.

Step 6. When you finish going through the crappy notes, rip out the page(s) and throw them away. You don't need them anymore because they are rewritten and you'll feel good about the progress you made.

I won't guarantee these steps will improve your grade, but I do guarantee that they will improve your understanding and knowledge of the material.

Additional thoughts:

A. Write in your textbooks, at least highlight important information. I used different colored highlighters for different purposes. Red was for definitions, blue was for what I thought were key concepts, green was for things referring to my class notebook. Will writing in your textbook reduce its value when you resell it? Well hopefully you will not resell it. Having that chemistry textbook could come in handy when you need to revisit something you forgot in your molecular biology class. If you absolutely do not want the book, why buy it in the first place? Probably you could borrow one from a colleague or use the library.

B. Scheduling. You need to prepare ahead of time when things are getting done. If you don't, you will almost certainly get behind or not have enough time. If you want to go to that party or game, you may need to start rewriting your notes earlier than normal to make sure you have enough time to finish before going out. Also, there will be several big assignments due for other classes throughout the semester, you'll need to be prepared for catching up on those notes you couldn't rewrite the day after class. (Don't get more than a class or two behind or you'll defeat the purpose of rewriting.)

C. Turn off your phone. You can survive an hour or two without reading all those awesome texts and facebook postings coming in. A 30 second distraction actually amounts to much longer, because it takes time to get back to where you were before you were distracted. Every time you break focus, you are back to a more superficial level of learning and it takes some time to get back to that deeper level.

C. Turn off your phone. You can survive an hour or two without reading all those awesome texts and facebook postings coming in. A 30 second distraction actually amounts to much longer, because it takes time to get back to where you were before you were distracted. Every time you break focus, you are back to a more superficial level of learning and it takes some time to get back to that deeper level.

D. When it's test time, you'll find it much easier to study. The material is already there in your mind because you've been through it at least twice already. You may have to pull an occasional all-nighter, but it will be different than the cramming you did previously.

Notes for a recently submitted grant

from a relevant paper.

|

E. For the record, I still use these techniques to prepare grants and papers (see photo). I do a lot of background reading and have notebooks dedicated to taking notes on the papers, complete with different colored pens. This allows me to make connections and think about the material in a much deeper way than I would be able to otherwise. Same for seminars I attend, I bring a notebook.

With those words of advice,

Good luck and have a great semester!

Poor Communication of Essentially Good Research

It is no surprise to see a press release on scientific research that inflates the conclusions of the study or its potential impact. But usually the basic biology is correct, not so with the press release I read today. (I thank the twitterverse for bringing this to my attention.) Since I'll go through the press release paragraph by paragraph, you can thank the twitterverse too,

The release starts out well enough, but quickly goes off the rails. In fact, the writers couldn't get out of the first paragraph, which is also the first sentence, without stating half-truths.

First of all, we have established that C. albicans adheres to things independently of infection. So a basic part of C. albicans lifestyle is to adhere to things, things like epithelial cells which are the structures C. albicans normally finds itself on. This is a function of biology not infection.

Second, this press release builds on a dead mythos that yeast cells are commensals and filaments are infectious. This was the conventional wisdom 20+ years ago, but the field has (or has tried to) move on. It is true the filamentous cells do things related to disease that yeast cells do not. Filamentous cells secrete gobs of proteases which help degrade the host tissues. Filamentous cells are invasive. But you know what, yeast cells do things related to disease that filamentous cells do not. Yeast cells do not stimulate the immune response as much as filamentous cells do. Yeast cell populations grow much faster than filamentous cell populations. Yeast cells can readily disseminate throughout the body via the bloodstream, filamentous cells cannot. But ignoring these facts, there are basic predictions we can make based on the press release premise. For example, we should not observe filamentous cells in non-diseased individuals, but we do. We should not observe yeast cells during bloodstream infections, but we do. Other fungal pathogens should show similar morphological transitions, they don't. In fact, Candida glabrata, the second most common Candida species causing human disease only grows in the yeast form.

Third, filastatin inhibits adherence and filamentation. This becomes problematic because those who work on C. albicans are already aware that filamentous cells are extremely adherent, but yeast cells are not. Thus, if you inhibit filamentation you by definition inhibit adherence. However the press release tells us why this result is really the SHITZ (emphasis mine).

In one case, the black bars, the cells were kept without (left) or with (right) drug for 8 hours and there is a profound difference between the two conditions. In the other case, the striped bars, the cells were grown for 4 hours and then drug left out (left) or added (right) and cells grown an additional 4 hours. Both samples lacking drug are similar (compare the leftmost of the black and striped bars). The authors suggest that the reduction observed 4 hours with drug (rightmost striped bar) represents a reversal of adherence, but this conclusion is not necessarily the best. How about growth after 4 hours is always ~8000 Fluorescence units, but when drug is added no further growth is observed. Knowing what the Fluorescence looked like at 4 hour in this experiment is lacking and important. Note the press release states the drug did something active, 'it knocked off many fungal cells already stuck to the polystyrene.' I say the drug inhibited growth or prevented additional adherence, like by preventing additional filamentous growth as observed in all the other experiments.

Look, I agree filastatin is an interesting molecule worthy of additional research and development as a coating for catheters and other medical devices. These are some interesting studies and the fact the drug does not appear to be toxic to human cell lines and in a mouse vaginal model is extremely encouraging. It is important to know how this drug acts systemically in a mouse because the bloodstream infections are the critical ones to combat. But these studies are an important first step.

Synergistically, √. Novel, √. Translational, √. Paradigm shifting, oops missed that one.

I feel bad, slightly, picking on this press release and the author statements. We often give answers to question that upon reflection wish we had a do over. However, this is my field of interest and C. albicans is the organism I primarily study, so I am intimately familiar with the issues in the field. I am sure the approach I take here could be applied to many press releases. I would like us, as scientists and communication officers, to work harder at getting the stories out, keeping it interesting and informative without jumping the shark. This likely requires some back and forth between the scientists and communications people with a touch of editorial oversight by an independent scientist.

The release starts out well enough, but quickly goes off the rails. In fact, the writers couldn't get out of the first paragraph, which is also the first sentence, without stating half-truths.

Targeting serious and sometimes deadly fungal infections, a team of researchers at Worcester Polytechnic Institute (WPI) and the University of Massachusetts Medical School (UMMS) has discovered a chemical compound that prevents fungal cells from adhering to surfaces, (This would be a great place for a period.) which, typically, is the first step of the infection process used by the human pathogen Candida albicans (C. albicans). (Red note by AbC.)The point being made is that 'adherence' is the first step of the infection process. Whatever the hell 'infection process' is escapes me, but it does sound pretty awesome and scary. However, the press release completely misses a key point, Candida albicans is a commensal in humans. C. albicans is easily culturable from 60% of all people and is almost certainly found in all humans. Let me be clear, C. albicans causes serious and sometimes deadly infections as noted in the first line of the press release. However, in the vast vast majority of people, C. albicans is not a problem. Herein lies the problem or obvious question ignored in order to write overimpactful press releases. Does C. albicans only adhere to surfaces during infection? Does C. albicans in most people simply float free in saliva, gastric juices, or vaginal fluids? (The answer to these questions is 'No'.)

After screening 30,000 chemical compounds in a series of tests with liveC. albicans, the team found one molecule that prevented the yeast from adhering to human cells or to polystyrene, a common plastic used in many medical devices. Named "filastatin" by the researchers, this molecule now emerges as a candidate for new anti-fungal drug development and as a potential protective material to embed on the surfaces of medical devices to prevent fungal infections.This is all pretty good. It hits on the major finding and the potential impact of the research. What is not explicit here, but comes up later, is that the major source of C. albicans in deadly systemic infections is contaminated medical devices, like catheters.

The team, led by co-principal investigators Paul Kaufman, PhD, professor of molecular medicine at UMMS, and Reeta Rao, PhD, associate professor of biology and biotechnology at WPI, reports its findings in the paper "Chemical screening identifies filastatin, a small molecule inhibitor of Candida albicansadhesion, morphogenesis, and pathogenesis," published online in advance of print by the journalProceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).Again nothing to complain about regarding the press release here. We are basically describing the leaders of the research teams and the source of the article. I do have an issue with part of the title of the paper 'a small molecule inhibitor of...morphogenesis...' The title suggests that filastatin inhibits the formation of cell structure or shape. In actuality, the drug inhibits the ability of yeast cells to form filamentous cells. This is a morphological transition, but it does not encompass the entirety of C. albicans structure and shape. A yeast cell making more yeast cells is an example of morphogenesis. The abstract makes this point clear, but the title is a bit colloquial. This is a problem in the field and not specific to the authors, I have probably used similarly short-hand.

"In humans, the most widespread fungal pathogen is Candida albicans, which is also one of the most frequent causes of hospital-acquired infections," the authors write. "We conclude that filastatin is not toxic to the human cell line under our assay conditions, but is unique in that it can impair fungal adhesion both to inert surfaces and to cultured human epithelial cells."I am not sure in what context filastatin is unique as a quick literature search revealed HIV-protease inhibitors, a 23 amino acid peptide, cranberry derived compounds, as well as antibodies have all been reported to inhibit C. albicans adhesion. (This is an issue of the authors inflating their work not of the press release writer(s).)

Infection by C. albicans causes common chronic illnesses like thrush and vaginitis, which affect millions of people globally each year and are not easily cleared by the handful of anti-fungal drugs now available. While most fungal infections do not cause serious harm, if one spreads to the bloodstream it can be deadly.All good. Minor issue with referring to thrush and vaginitis as chronic illnesses as the vast majority of cases are not chronic.

Hospitalized patients with catheters or central intravenous lines are at risk as the fungi can grow on those devices and enter the body. Similarly, patients with implanted medical devices like pacemakers or prosthetic hips or knees are also at risk if the implant carries a fungus into the body. Also, people with compromised immune systems are at greater risk for serious fungal infections. Because of the lack of effective drugs against C. albicans and other pathogenic fungi, the mortality rate for systemic fungal infections is between 30 and 50 percent.Again all good, but now we come to it. The paragraphs of FAIL.

Typically, a blood stream infection of C. albicans or a similar pathogen begins with fungal cells attaching to a surface—a catheter, for example, or epithelial cells lining the mouth—to form what is known as a biofilm. Next, the ovoid shaped yeast cells morph into an invasive filamentous form, extending pointed filaments that penetrate and damage surrounding tissues. In the current study, the team found that filastatin curtailed both steps: it largely prevented C. albicans from adhering to various surfaces, and it significantly reduced filamentation (inspiring the name filastatin).

First of all, we have established that C. albicans adheres to things independently of infection. So a basic part of C. albicans lifestyle is to adhere to things, things like epithelial cells which are the structures C. albicans normally finds itself on. This is a function of biology not infection.

Second, this press release builds on a dead mythos that yeast cells are commensals and filaments are infectious. This was the conventional wisdom 20+ years ago, but the field has (or has tried to) move on. It is true the filamentous cells do things related to disease that yeast cells do not. Filamentous cells secrete gobs of proteases which help degrade the host tissues. Filamentous cells are invasive. But you know what, yeast cells do things related to disease that filamentous cells do not. Yeast cells do not stimulate the immune response as much as filamentous cells do. Yeast cell populations grow much faster than filamentous cell populations. Yeast cells can readily disseminate throughout the body via the bloodstream, filamentous cells cannot. But ignoring these facts, there are basic predictions we can make based on the press release premise. For example, we should not observe filamentous cells in non-diseased individuals, but we do. We should not observe yeast cells during bloodstream infections, but we do. Other fungal pathogens should show similar morphological transitions, they don't. In fact, Candida glabrata, the second most common Candida species causing human disease only grows in the yeast form.

Third, filastatin inhibits adherence and filamentation. This becomes problematic because those who work on C. albicans are already aware that filamentous cells are extremely adherent, but yeast cells are not. Thus, if you inhibit filamentation you by definition inhibit adherence. However the press release tells us why this result is really the SHITZ (emphasis mine).

As a next step, the team tested filastatin's impact on C. albicans cells that had grown unfettered in test wells and had already adhered to the polystyrene walls. When the compound was added to the culture mix, it knocked off many of the fungal cells already stuck to the polystyrene. The inhibitory effects of filastatin were further tested on human lung cells, mouse vaginal cells, and live worms (C. elgans) exposed to the fungus to see if it would reduce adhesion and infection. In all cases, the novel small molecule had significant protective effects without showing toxicity to the host tissues.Based on the bolded statement, you now think 'HOLYFUCKBALLS, that's interesting,' because the cells were already stuck to something. While the press release is technically correct, the implications are flat out wrong. First, in almost every experiment the drug was present throughout the experiment, in other words as soon as the cells were added, aka before adherence occurred. Thus, inhibition of filamentation is an obvious and unsurprising likelihood to explain these data. Second, in the one experiment referred to above, the effect of the drug was minor (see data from paper below). Even this minor effect could be an attribute of growth.

|

| From PNAS Figure 2D |

Research is now focused on teasing out the precise molecular mechanisms filastatin uses to prevent adhesion and filamentation. "We need to find the target of this molecule," Rao said. "We have some good leads, and the fact that we aren’t seeing toxicity with host cells is very encouraging, but there is more work to be done."Why does the target of filastatin need to be found? It seems important, but I am not sure why and I wonder if a general audience reader knows why.

Additional studies on filastatin are underway at both WPI and UMMS. "The molecule affects multiple clinically relevant species, so we're pursuing the idea that it provides a powerful probe into what makes these organisms efficient pathogens," Dr. Kaufman said. "In this era of budget gridlock in Washington, our ability to get funding from the Center for Clinical and Translational Research at UMMS to support this work was essential for allowing us to pursue our ideas for novel ways to approach this important class of hospital-acquired infections."What makes these organisms efficient pathogens? These organisms are shit pathogens. Virtually no one had issues with deadly fungal infections before the 1960s and even after 1960 that number was minute. It is only recently that these organisms have risen to the forefront of importance and it's not the organism that has changed. Rather it is the host, us, or more specifically modern medicine that is the culprit. Now we have a large and growing population of people who are immunocompromised because of cancer therapy, organ transplants, HIV, even extreme old age. But as noted 'in this era of budget gridlock in Washington,' we must inflate and oversell our studies 'to get funding from the Center of Clinical and Translational Research....' There fixed it.

Look, I agree filastatin is an interesting molecule worthy of additional research and development as a coating for catheters and other medical devices. These are some interesting studies and the fact the drug does not appear to be toxic to human cell lines and in a mouse vaginal model is extremely encouraging. It is important to know how this drug acts systemically in a mouse because the bloodstream infections are the critical ones to combat. But these studies are an important first step.

The project was also funded by a grant from a WPI/UMMS pilot program established to promote collaborations between researchers at the universities to advance early stage translational research. "Joint research programs, such as the pilot program between our institutions, are central to WPI's work in the life sciences," said Michael Manning, PhD, associate provost for research ad interim, at WPI. "As this collaboration between Professors Rao and Kaufman demonstrates so well, both institutions can leverage their complementary expertise for the ultimate advancement of scientific discovery and public health."

Terence R. Flotte, MD, UMMS executive deputy chancellor, provost, and dean of the School of Medicine, agreed. "The faculty of UMass Medical School and WPI possess scientific knowledge and expertise in disciplines that complement each other," he said. "The creation of this type of multidisciplinary team collaboration between the two universities allows us to work synergistically to solve problems important for improving human health."

Synergistically, √. Novel, √. Translational, √. Paradigm shifting, oops missed that one.

I feel bad, slightly, picking on this press release and the author statements. We often give answers to question that upon reflection wish we had a do over. However, this is my field of interest and C. albicans is the organism I primarily study, so I am intimately familiar with the issues in the field. I am sure the approach I take here could be applied to many press releases. I would like us, as scientists and communication officers, to work harder at getting the stories out, keeping it interesting and informative without jumping the shark. This likely requires some back and forth between the scientists and communications people with a touch of editorial oversight by an independent scientist.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)